Wrong Thing, Right Space

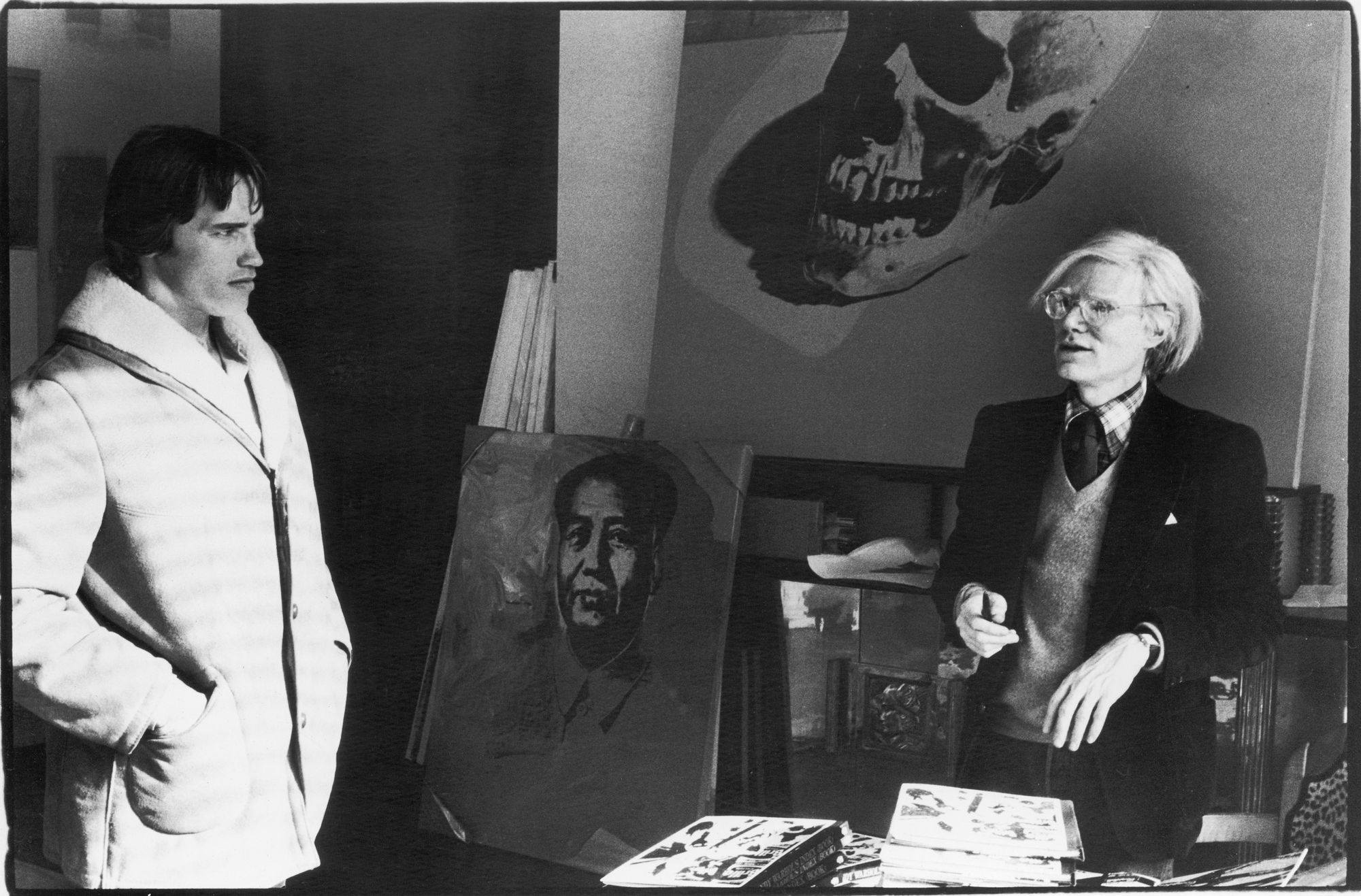

Andy Warhol, Arnold Schwarzenegger, 1977.

On an unseasonably warm evening in New York City, February 25th, 1976, spectators began arriving at the Whitney Museum of American Art for an unusual event. Articulate Muscle: The Male Body as Art was described on posters as a “live exhibition” by three bodybuilders—Frank Zane, Ed Corney, and Arnold Schwarzenegger—all champions in the sport but little-known outside the practice’s insular community.

Articulate Muscle had been devised to promote and generate funding for George Butler and Robert Fiore’s half-finished documentary Pumping Iron. By 1976 the Pumping Iron filmmakers had shot their footage but ran out of money for its editing. (The documentary was adapted from a book of the same name, published two years before, written by Charles Gaines with photographs by Butler.) Trying to fundraise any way they could, Butler and Fiore held private screenings of the work in progress in the offices and living rooms of friends of friends from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco and cities in between. The Minneapolis Star Tribune, reporting on one such gambit, noted dryly that “Minneapolis isn’t traditionally regarded as a city of angels—not the financial kind, and that after Butler screened some dailies for a perplexed group of potential investors, the response was muted. "God, no," replied one man when asked if he might take a flyer. "I didn’t know they were trying to raise money tonight. I thought they were just showing some Schwarzenegger recounts in his memoir how, in light of their disappointing fundraising efforts, “rather than give up on the project, [Butler] hit on the idea of staging a posing exhibition in a New York City art museum to try to attract wealthy

By the day of the event, the museum had sold only a handful of tickets and expected just a couple hundred people to attend. Instead, visitors showed up in droves, crowding the lobby, and then the museum’s entrance, and then the sidewalk along Madison Avenue. As it got closer to the starting time, with more than one thousand people already in attendance, it became clear there were too many people to fit into the gallery and guards closed the doors to any more visitors, leaving hundreds more locked out. Harried admissions clerks, their cash registers overstuffed with small bills, began tossing money into unruly piles as people rushed by them to claim a space in the huge, now overflowing room that had until recently displayed monumental sculptures by Mark di Suvero.

Excited visitors arranged themselves on the floor, crowded into ever-widening concentric circles around a low, revolving dias. The room was populated by an eclectic and sizable mix of serious bodybuilding fans and a smaller but powerful constituency of New York’s cultural class. Curator Lawrence Alloway, widely credited with coining the term “pop art,” and whose writing about art pushed back on the strictures of modernism to make way for something new, attended with his wife, feminist painter Sylvia Sleigh, known for her images of male nudes. Douglas Crimp was there, then an art history graduate student who would, within a year, curate Pictures, a groundbreaking exhibition downtown, widely heralded as launching the postmodern art movement. Then-emerging photographer Robert Mapplethorpe was in attendance (invited by the authors of Pumping Iron, who had published bodybuilding images from his collection of historic photographs in their book), as was novelist Kurt Vonnegut. Along the back wall of the space sat a number of eminent academics and art historians, arranged at a long bank of tables covered in white tablecloths, their names on paper tents facing the audience. Vicky Goldberg, art critic for the New York Times, who had already written about bodybuilding for the paper, was there, while Gaines, the Pumping Iron author, waited at the ready to emcee the night. In his memoir, Schwarzenegger recalls one other significant attendee, who he refers to in his account of Articulate Muscle as onlookers from “the New York art scene,” specifically “critics, collectors, patrons, and avant-garde artists like Andy

It is meaningful that out of all the faces in the crowd it was Warhol who Schwarzenegger noticed that night; Warhol certainly noticed him. Arguably no one was better placed than Warhol to appreciate the unlikely emergence of the bodybuilder into New York’s art world, not only because of Warhol’s life-long fascination with both beautiful men and Hollywood stars, but also because of something more integral to Warhol’s practice. Just the year before Articulate Muscle—about a decade into an art career characterized by frenetic production, catholic approach to medium, headline-grabbing society appearances, and polarizing ubiquity—Warhol had published a book of quips, aphorisms, and anecdotes titled The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, in which he explained his professional strategy:

I like to be the right thing in the wrong space and the wrong thing in the right space…. Usually being the right thing in the wrong space and the wrong thing in the right space is worth it, because something funny always happens. Believe me, because I’ve made a career out of being the right thing in the wrong space and the wrong thing in the right space. That’s one thing I really do know

Warhol had effectively spent his career testing out theories about the power of being out of place, whether by displaying Brillo boxes and soup cans in galleries, appropriating photojournalism onto canvases, or screening art films in commercial cinemas. His work forced a decisive break with modernism and ushered in the heady, context-obsessed postmodern art movement. Schwarzenegger, appearing incongruously greased-up and gorgeous on a museum pedestal, was a perfect example of Warhol’s wrong thing, right space strategy in action—and one that, unlike Warhol’s experiments in re-signifying everyday items into art, used his strategy to move far beyond questions about art, and beyond the art world as well. Schwarzenegger wasn’t fundamentally interested in being seen as art by the art world; he wanted to be seen by the world. Warhol took note.

Beyond the obvious “wrongness” of this bodybuilder flexing in the white cube of the Whitney, Schwarzenegger resonated with another of Warhol’s pop-cultural observations from his Philosophy when he noted that, “All the movie stars are trying to become race-car drivers. And besides, all the new movie stars are the sports people, the exciting people—and they make the most Warhol was particularly attuned to the crossover ambitions of strivers like Schwarzenegger—who had explicit professional aims to move from bodybuilder to movie star to politician. Warhol had used that operation many times throughout his own career, leveraging success in one field to stand out in another, largely by being the “wrong thing” in the new space: transitioning from commercial artist to painter to filmmaker to author to manager of a rock band to magazine publisher to TV talk show host to fashion model, and so on. This also worked to help make the people around him famous. Almost from the moment of his earliest pop art successes Warhol was a social as well as artistic force in New York culture, one so powerful as to draw others into his slipstream, making celebrity—his own, and others’—both the subject and outcome of his practice, his thesis in action.

In the 1960s, Warhol went about proving just that, by anointing some of his more charismatic friends and hangers-on—Edie Sedgewick, Candy Darling, Nico, and Viva—his “superstars.” He used his own films, interviews, and press events to turn them into minor local celebrities, largely by the transitive powers of his own fame. Schwarzenegger offered a much more ambitious ready-made test of Warhol’s hypotheses about standing out—and if Schwarzenegger’s attempt at stardom was the immense natural experiment Warhol had been waiting for, Warhol was the mad scientist, ready to record his observations in the lab.

*

It was clear to Warhol and all the other art world attendees that this night was going to be different from the usual Whitney fare. The gallery thrummed with anticipation and body heat as the last attendees in the door wedged themselves into what little space was left. Then, after all the waiting and squeezing in, Articulate Muscle commenced—only, much to the audience’s obvious surprise and dismay, it began with a panel discussion about how bodybuilding fit into the canon of art. As eminent art historians droned on in what one sports journalist called “scholarly expounding on neoclassical forms and traditions of the male nude, the audience became restive. Bored visitors started muttering softly to themselves, then complaining at volume. “Give us shouted someone from the floor.

The panel, instead of revealing fundamental similarities between the art and bodybuilding worlds, as the show’s organizers had hoped, had made clear how cloistered each of these worlds actually was—how rarely the elitist art world allowed the outside world in, and how bodybuilding’s own arcane codes kept potential fans out. Newsday’s coverage of the event bluntly described the clash of subcultures with a troubling reinscription of identity-based hierarchies:

Never before has there been such a crowd at a onetime Whitney Event. Certainly never such a predominantly blue-collar crowd. They’ve come in their T-shirts and flowered synthetics. The women sometimes in wide-skirted taffeta cocktail dresses out of the ’50s…. But there are also pristine women in patent leather Gucci shoes and little wool dresses from Bonwit’s, a sprinkling of obvious gays, a contingent of rising young men in pin-striped suits, some women in wheelchairs and on crutches—and the bodybuilding groupies. Hardly anyone is past

Matthew Baigell, one of the panelists, recalled that at first the discussion seemed like it would be “fun, until the audience started to get angry and storm the The panel was hastily cut short and, at long last, the posing finally began.

What followed was precisely what the audience had been waiting for: muscles. The relieved audience burst into applause when Gaines called each bodybuilder to the room for his turn to pose: first Zane, whom Gaines hailed for his symmetry; then Corney, who flowed gracefully from one position to the next; and finally Schwarzenegger, the winningest of the three athletes. When it was his turn, Schwarzenegger bounded out from the dressing area just outside of the gallery wearing only his nutmeg-colored posing briefs. Astonished gasps and flash bulb flares ricocheted around the room. He mounted the pedestal in the center of the floor and gracefully assumed his first “shot,” holding the pose patiently as the motorized lazy Susan rotated him like a second hand turning around a dial.

In some images of the night, Schwarzenegger looks naked because his unobtrusive brown posing briefs blend in with his meticulously tanned, taut skin. The event’s striking lighting, a spotlight set above the platform, ensured that Schwarzenegger’s swollen muscles cast deep shadows on his otherwise glistening skin, slick from the oil he’d applied to his body. His hair, which is long and also brown, ripples, wavy like the muscles on his back, biceps, and legs, all the tawny surfaces only reinforcing the overall impression of mass in front of the viewer. Schwarzenegger undulated through a series of poses he and the other bodybuilders had planned for the evening, recalling in his memoir that:

We wanted each pose to look like a sculpture, especially because we were on a rotating platform… I hit the standard shots and showed off some of my trademark poses… I wrapped up my ten minutes with a perfect simulation of The Thinker by Rodin and got a lot of

In photographs of the event, audience members beam up at Schwarzenegger on the posing dais. Whole sections of the audience tilt their heads in unison, following the lines of Schwarzenegger’s twisting body as if he is pulling them with strings. Posing in the Whitney’s gallery, with its iconic coffered ceilings, crisp white walls, and heroic scale, Schwarzenegger’s body paradoxically appears both hard and human, and makes clear how unusual it is to see a living, breathing body exhibited in a museum—the wrong thing in the right space.

*

This was precisely why Warhol wanted to meet him. In the weeks after the Whitney event, the publicity agent for Pumping Iron, Bobby Zarem, began taking Schwarzenegger around town, recalling in an interview, “I pretty much introduced him to the art Zarem took Schwarzenegger to Elaine’s, the storied uptown restaurant and hangout of film stars, literati, and other New York celebrities, where he was introduced to Warhol. In his memoir Schwarzenegger recalled that Warhol asked about Articulate Muscle and “wanted to intellectualize it and write about what it meant.” He questioned, “How can you look like a piece of art? How can you be the sculptor of your own

While Warhol was curious about the reframing of bodybuilding as art, he was even more interested in Schwarzenegger’s hopes for the future. He was 28 at the time of the Whitney exhibition, and while he was a champion bodybuilder, he remained little-known outside the niche sport’s community. He was also enormously ambitious, the Pumping Iron documentary just one step in a carefully plotted, multiphase process of getting where he wanted to go, from his poor childhood in postwar Austria to the greatest reaches of the American Dream through his oft stated plan to use his bodybuilding prominence to “become a movie star, make millions, marry a glamorous wife, and wield political

Warhol became an informal mentor to Schwarzenegger, inviting him to visit the Factory, Warhol’s studio then located in Union Square, and taking him under his wing following the usual playbook: bringing Schwarzenegger to Manhattan hotspots where they were sure to be noticed, like Studio 54; photographing him in the Factory with his Polaroid and around town with his Minox; and detailing his encounters with Schwarzenegger in his oral diary, which was transcribed and published after Warhol’s death.

Warhol even promoted Schwarzenegger’s nascent acting career in the December 1976 issue of his magazine, Interview, months before Pumping Iron had even been released. The profile emphasized Schwarzenegger’s crossover appeal and suggested that Schwarzenegger, with his muscles and on-camera experience, would be perfect to play Superman. (Interestingly, in that interview Schwarzenegger was already concerned about typecasting and the kinds of roles he might be offered once Pumping Iron made him the star he felt sure to become, explaining, “I think if I would do Superman now that’s what I would be known as—just

Schwarzenegger started hanging out regularly at the Factory. Vincent Fremont, Warhol’s studio manager at the time, recalls, “We saw a lot of Arnold…. He was very charismatic. You couldn’t mistake that at all. He had a big smile and was very Zarem had also placed a story about Schwarzenegger in Newsweek for an upcoming issue in 1977 and got the painter Jamie Wyeth a commission to paint him for the cover. Warhol had already loaned Wyeth an unused corner of the Factory to work in, and so Wyeth painted him there—setting up his easel by one of the big windows over Union Square, sectioned off with some makeshift cardboard partitions, and inviting Schwarzenegger to pose.

Schwarzenegger enjoyed being in the Factory’s hive of activity. On breaks from posing for Wyeth, Schwarzenegger would “walk around and talk to people” in the Factory offices. Sometimes he would even man the phones. “Schwarzenegger was a big flirt,” Fremont recalls:

He was always walking around the Factory without his shirt on. Everybody loved him at this point. He was a new phenomenon and he was out there being very charming and really putting himself in the spotlight…. But he hadn’t attained his stardom yet. He was on his way up…. He was very approachable and wanted the

Schwarzenegger spent hours at a time oiled up and illuminated by the light from the window out onto Broadway, flexing for Wyeth as Warhol, his friends, and his staff buzzed around and New York bustled outside. Fremont recalls, “You could be walking down Broadway and if you reached Broadway and 17th and you looked up, you’d see Arnold While Wyeth’s portrait was not ultimately used for the publication, the painting was exhibited in November 1977 at the Coe Kerr Gallery uptown, whose proprietor recalled what Schwarzenegger had told him about the posing experience:

Jamie placed him by a window for the effect of light, and Arnold, his eyes are sort of looking out the window, down towards the street where constantly during the pose there were hundreds of people looking up at him…. He said that probably it was one of the most difficult things he’s ever done, to pose by the hour for an artist. It’s a very difficult thing to do, just to stand there without moving and looking out at an adoring public looking up at

One afternoon in 1977, Warhol invited Schwarzenegger into one of the Factory’s back rooms to watch him shoot photographs for what ultimately became Warhol’s Sex Parts work, a sometimes explicit series of details of body parts that started out as a somewhat tamer project to abstract nudes into unidentifiable formal properties, works Warhol initially called Landscapes. Schwarzenegger followed him into his studio for the shoot, where six young men were disrobing. In his memoir Schwarzenegger remembers telling himself, “‘I may be part of something interesting here…. God has put me on this path. He means me to be there, or else I’d be an ordinary factory worker in Schwarzenegger watched from the side as Warhol arranged the naked men on a white table, laying them on top of each other in a confusing jumble of limbs and flesh, adjusting their positions, then the lights, and shooting a number of Polaroids. When Warhol showed one to Schwarzenegger, the Austrian was surprised by how the men “didn’t look like people, just shapes…. I said to myself, ‘This is unbelievable, this guy is turning asses into rolling

The improvisational, lightning-in-a-bottle nature of so much of Warhol’s practice made an impression on Schwarzenegger, who recalled the unpredictable opportunity:

I had the feeling that if I’d asked in advance to watch him work he’d have said no. With artists, you never know what reaction you’ll get. Sometimes being spontaneous and jumping on an opportunity is the only way you can see art being

While Schwarzenegger’s goals for his life had long been clear to him from his earliest adolescence, what Warhol helped him see was not the places he wanted to take his life but a roadmap for how to get there. Not only did Warhol offer generous and meaningful publicity early in his friend’s career; his theories about standing out and crossing over also illuminated Schwarzenegger’s path forward and provided a framework for Schwarzenegger’s future efforts to raise his profile. This became his longterm strategy, evinced equally in films which capitalized on his unusual person (from 1984’s Terminator, in which he plays a muscular cyborg-assassin loose amongst mere humans, to 1990’s Kindergarten Cop, in which he was cast as an undercover policeman infiltrating a class of five year olds) and in gubernatorial campaign pronouncements like, “I’m a different kind of candidate. I’m not a traditional

Warhol offered Schwarzenegger a high-profile model for how to use being out of place to his advantage, and for that one formative year they spent together, from first encountering him at Articulate Muscle to Pumping Iron’s successful New York première, Schwarzenegger studied his friend closely. In 1977, after Pumping Iron had debuted to great acclaim and he was widely celebrated as “a unique and credible physical star… enjoyed and admired by a vast cross section of the Schwarzenegger was asked by a journalist about his relationship to the artist. The bodybuilder paused and then explained, “It all has been a very educational thing for me getting to know Andy Schwarzenegger offered Warhol something too: he proved Warhol’s wrong thing, right space theory right on a scale that took many, if not Schwarzenegger, by surprise.

After their first year of friendship, as Schwarzenegger spent more time in Hollywood and his career moved from one box office triumph to another, the men kept in touch. Schwarzenegger started dating Maria Shriver, who was not only beautiful but also a smart and ambitious member of the Kennedy clan, a storied American political dynasty of Democrats in which Schwarzenegger (muscle-bound actor, recent immigrant, Republican) was not a natural fit. When Schwarzenegger and Shriver got engaged, it was Warhol whom Schwarzenegger commissioned for her wedding gift: her portrait, in series. And in 1986 when Shriver became the “glamorous wife” of Schwarzenegger’s dreams in a small but opulent wedding, Warhol was there.

He died one year later. By then Warhol had witnessed Schwarzenegger become so many of the things he had hoped to be—a wealthy Hollywood star with a striking spouse—something he had achieved at least in part with Warhol’s strategic help. And Schwarzenegger kept moving forward through his list, going into politics just as he predicted. While Warhol wasn’t alive to witness Schwarzenegger’s brief and tumultuous campaign for governor of California in 2003, pundits and pollsters acknowledged the outsize role name recognition from his Hollywood stardom and longtime presence in visual culture played in the campaign; in a field crowded with one 135 mostly unknown candidates, Schwarzenegger stood out.

In his lifetime, Warhol had already watched his right thing, wrong place strategy lift Ronald Reagan—Schwarzenegger’s political hero, a sports star turned actor turned politician—to the U.S. Presidency. Schwarzenegger’s successful campaign would likely not have surprised him. And Warhol’s strategy remains evermore effective today, as popular culture’s power is turbocharged by the connectivity and celebrity-boosting power of the Internet. Real estate developer and reality TV star Donald Trump successfully leveraged his own name to become the 45th President of the United States, in just one recent example with far-reaching consequences. So, while Schwarzenegger was not the first celebrity to use his fame to recontextualize himself into a populist legislator—and his fans into constituents—neither will he be the last.

And though Warhol wasn’t there to see it happen, Schwarzenegger didn’t forget his friend’s early help in finding his way to the place he wanted to go. Even in the statehouse in Sacramento, he remembered.♦

Subscribe to Broadcast