Gazing Starward in the City That Never Sleeps

A note from Janna Levin, Pioneer Works Director of Science and Broadcast Co-Editor-in-Chief:

In an inspired, Fitzcarraldian ambition, Pioneer Works plans to hoist a stunning observatory atop the former factory originally named Pioneer Iron Works. Like Fitzcarraldo’s opera-blaring steamboat in the Amazon, the astronomical observatory is a celebration of culture for all. The centerpiece will be a restored antique telescope of exceptional provenance. Built at the peak of telescope manufacturing in the 1890s, the nearly sixteen-foot long telescope retains the original hand-ground lenses of remarkable quality. The detailed and impressive mechanicals are also all original and traceable to their famed manufacturers. The telescope is an enthusiast’s delight: a phenomenal, historic, museum-quality artifact.

Anyone who has had the privilege of leaning into the eyepiece of a massive, antique telescope to peer at celestial bodies—the moon, Jupiter, Saturn, comets—will understand the romance and visceral impact of the experience. Very few people ever have such an opportunity. The Pioneer Works Observatory—a public observatory the likes of which New York City has never seen despite nearly a century and a half of thwarted attempts—will offer that magical experience, free and available to all.

The telescope is from the same era as our building and represents a zenith in mechanical engineering. In nineteenth-century America, astronomical observatories had become something of a craze and, despite an intriguing history of bold attempts to manifest a grand observatory in the bustling metropolis around Brooklyn and Manhattan, none succeeded. To honor that history, as Pioneer Works forges a vision for a twenty-first-century observatory, Broadcast commissioned science writer, historian, and antique telescope enthusiast, Trudy E. Bell, to reflect on New York City’s observatories that might have been.

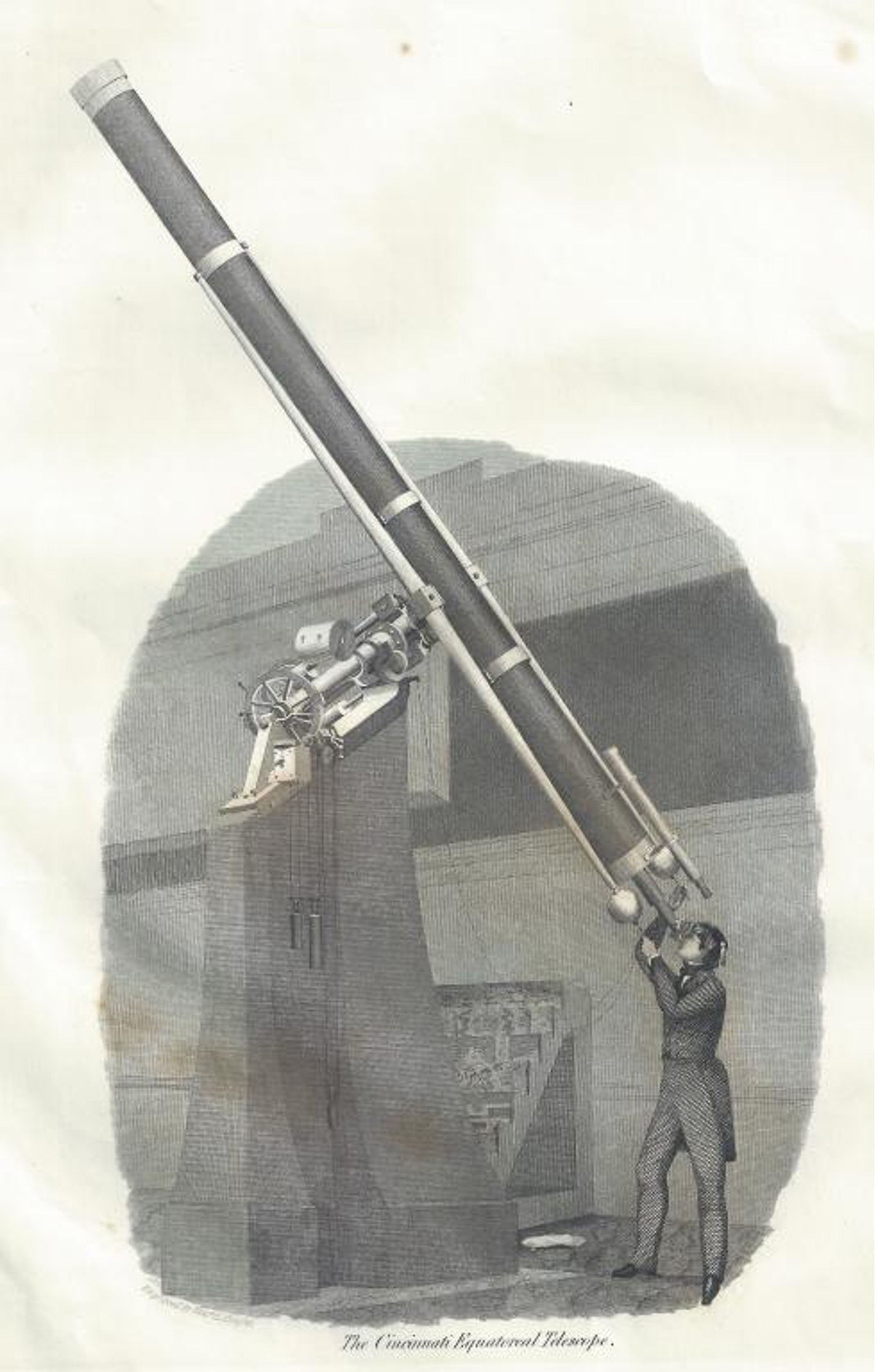

In 1842, residents of the booming city of Cincinnati, in what was then the far-western state of Ohio, raised enough money in three weeks to order an exquisite German-made refracting telescope with an aperture of eleven inches. When the magnificent instrument was mounted in the Cincinnati Observatory in 1845, it was the largest in the United States. Two years later, in 1847, the Harvard College Observatory mounted its new fifteen-inch refractor as one of two largest in the entire world (the other being in Russia).

Not to be outdone, also in 1847, leading citizens of Brooklyn, New York, met “to take immediate measures for the erection of an observatory in the city of Brooklyn,” which should be “superior to any in the world.” They estimated that “the amount necessary to be raised, independent of a suitable site will be $40,000,” to be raised by subscription, a form of selling shares of stock.

That fundraising goal was breathtaking. By comparison, in 1843, the Harvard College Observatory had subscribed more than $25,000 in just six weeks. In 1845, in Washington, DC, the federal government had completed the US Naval Observatory, costing $25,000 and financed by tax dollars, the country’s national observatory. In fact, by the 1840s, the entire nation was in a full-fledged observatory-building movement that lasted well into the 1890s.

The envisioned Brooklyn Observatory, however, was never built. Moreover, the ill-fated Brooklyn Observatory was one of at least half a dozen nineteenth-century attempted observatories in the New York City area that were public in some sense—funded either by pooled philanthropy of the citizenry or by tax revenues, or intended in part for the public good (such as determining local standard time, or public education)—and planned for Manhattan, Brooklyn, or Staten Island. But none of the five jurisdictions that in 1898 consolidated to become the five boroughs of modern New York City ever succeeded in building a public observatory—although multiple private individuals and schools constructed observatories for their own use.

Especially intriguing are the most ambitious observatory-building attempts that failed despite securing major financial and political backing, scientific and public support, donated land, and legal permissions. The rise and fall of the three largest never-built public New York metropolitan area observatories proposed between 1847 and the first world war—the Brooklyn Observatory, the New York Astronomical Observatory in Central Park, and the observatory of the Brooklyn Institute (now the Brooklyn Museum)—is a tale of great passion and mislaid dreams. But why in the first place did so many individuals and institutions in nineteenth-century America want to build astronomical observatories? Diverse but coinciding motivations mutually reinforced their desire.

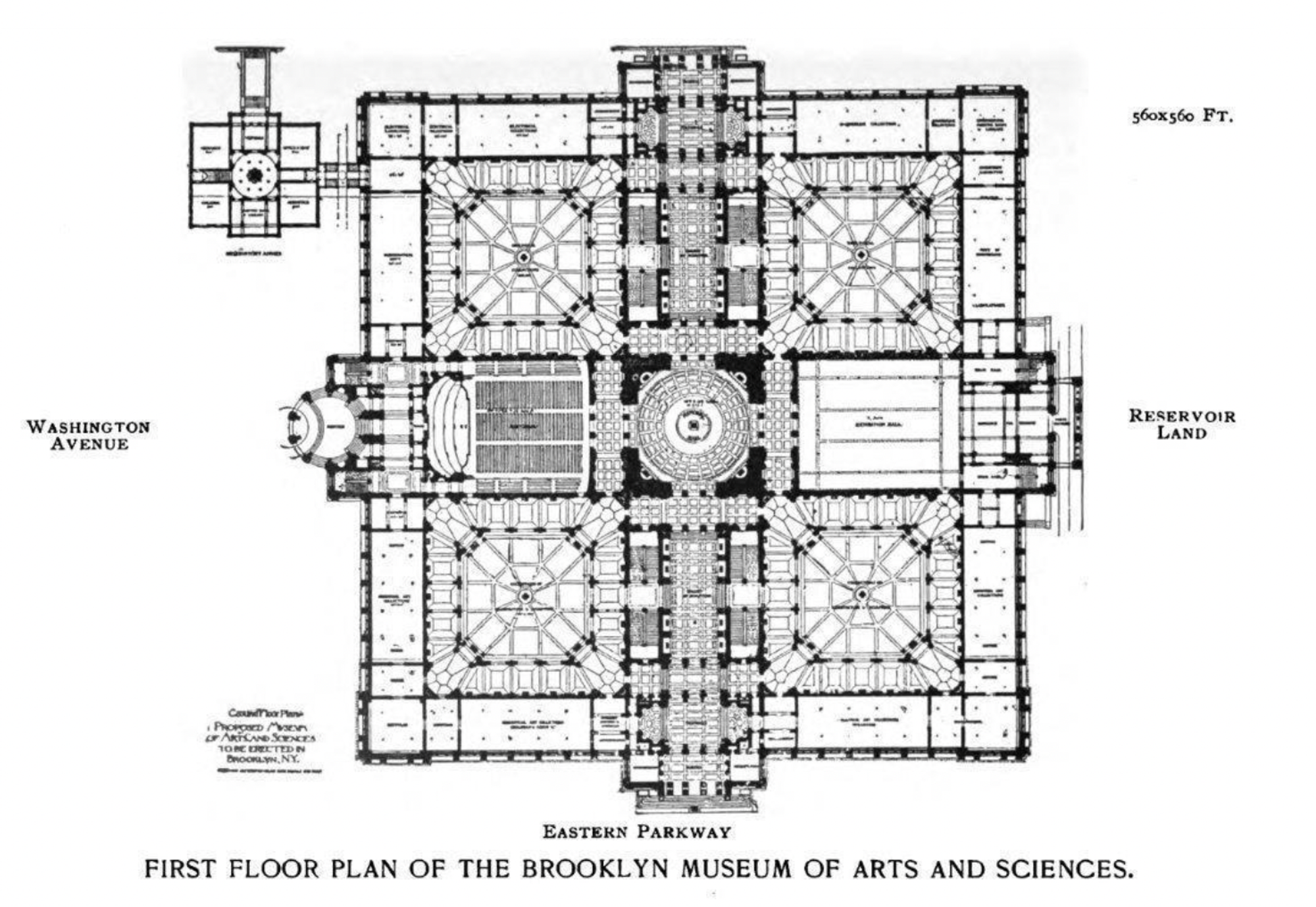

The initial (1893–94) floor plan for the Brooklyn Museum (north is at the bottom) envisioned a museum much larger than what was ultimately built. It also included an Observatory Annex to the southeast (upper left), later relocated to the southwest of the main building. Although the annex is dwarfed by the enormous main building, the observatory was originally planned to be 150 by 70 feet, with a central dome large enough to shelter a proposed 18-inch refractor.

Source: The Sixth Year Book of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, 1894 (Brooklyn: Published by the Institute): frontispiece.*

The nineteenth century was astronomically spectacular. There were several brilliant comets, some visible for weeks even in the daytime; a dramatic “rain of fire” Leonid meteor shower in 1833; the highly publicized and controversial discovery of the major planet Neptune in 1846; and discoveries throughout the century of a growing number of minor planets (asteroids), binary star systems, and mysterious variable stars that kept changing their brightness, some quite dramatically. Moreover, in that agrarian age before the advent of smoky industrial centers and widespread street lighting, night skies were velvet black and star filled; thus, flickering auroras (northern lights), falling stars, ghostly comets, and other astronomical marvels were visible to anyone who simply stepped outdoors and looked up. Moreover, astronomy was essential in daily life for telling time, determining cycles of planting and harvest, fixing the dates of religious observances (such as Easter), and precise astronomical observations were crucial to such professions as surveying, navigation, and map making.

US society was also at that time in the throes of several religious great awakenings and revivals, and was generally receptive to ongoing scientific developments, evidence of the wondrous majesty of a Creator God. Well into the late nineteenth century, Christian religious beliefs—especially those of evangelical Protestant denominations—were highly influential in elementary and higher education and in public life. Astronomical observatories were exalted as spiritual sanctuaries for lifting one’s thoughts to a higher plane. They were a way, as one of their leading exponents at the time, the astronomer Simon Newcomb, put it, to “enjoy the fresh air of heaven.” They were thought of as places for coming to know God personally and directly by beholding His works as well as His Word. When Northwestern University’s Dearborn Observatory was dedicated in 1888, M. D. Johnson, president of the Chicago Astronomical Society, writes that its builders hailed their creation as “a moral institution, an ally of the biblical institute.” It’s little wonder that observatories were often named to honor distinguished professors or donors, or seen as worthy memorials to deceased loved ones at their alma maters.

Both before and after the Civil War, the nineteenth century was the heyday of the US industrial revolution. Along with the development of such technologies as the railroads, the telegraph, and electric power, innovations in nineteenth-century glass making, steel making, and engineering design enabled the giant refracting telescope. Better yet, superb US telescope makers were taking the lead in advancing precision optics and mechanics. In the mid-nineteenth century, European observatories began ordering and installing instruments fashioned by American artisans—a boundless source of national pride. By the century’s end, American-made instruments came to dominate worldwide.

Both the Brooklyn Observatory and the New York Astronomical Observatory in Central Park were inspired by the example of one Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel (1809–1862) and his never-say-die commitment to building, using, and publicizing the Cincinnati Observatory as its founding director. Mitchel was an astronomer and a brilliant astronomical orator who has been called the Carl Sagan of the nineteenth century for his wildly popular lectures, which in the 1840s and ’50s attracted rock-star-sized audiences in a dozen cities.

Mitchel garnered worldwide fame between 1842 and 1845 for spearheading the incorporation of an astronomical society to found the Cincinnati Observatory, financing the effort by selling shares of stock at $25 each—roughly equivalent to a month’s earnings for a day laborer. To minimize risk and entice subscribers, Mitchel declared that subscriptions would not become binding until three hundred shares had been pledged to raise an initial $7,500. Through intensive door-to-door personal effort, Mitchel secured all the subscriptions he needed, in just three weeks, to travel to Bavaria and secure a state-of-the-art instrument that became the center of his observatory. Just before the telescope arrived, the school where he taught, Cincinnati College, burned to the ground—but he persevered, supporting himself and the building of the Cincinnati Observatory with his lectures.

The Cincinnati Observatory’s eleven-inch (sometimes called a twelve-inch) refracting telescope was the largest in the United States when it was mounted in 1845. The fundraising methodology of its director Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel inspired the founding of other proposed US observatories, including ones in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Source: Sidereal Messenger 1(7), 1846, frontispiece.In part through Mitchel’s own continual retelling in his lectures, the story of his success grew to have the power of living myth: how in three short years, one bantam runt of a man with boundless energy and nerve overcame tragedy by taking enormous personal gambles, and labored shoulder-to-shoulder with his workmen to construct a major observatory in what was then the US western frontier. If one determined soul could accomplish all that in the grubby backwater boomtown of Cincinnati, what heights might another achieve in a wealthy educated cosmopolitan eastern metropolis?

*

Several cities—including Brooklyn and New York City, then distinct municipalities—modeled their own fundraising efforts on the organizational structure and methods that had worked in Cincinnati, a methodology of community philanthropy later dubbed “civic astronomy.” Some cities even invited Mitchel to lecture specifically to raise funds for their own observatory ambitions.

Until Brooklyn was absorbed into greater New York in 1898 , it was a fast growing, wholly independent city with its own cultural ambitions. Moreover, Brooklyn residents strongly resisted their city being overshadowed by nearby larger Manhattan. In 1847, they readily embraced the vision of constructing a major astronomical observatory so that, in the words of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper, “our city may no longer be known from its proximity to New York, but by its observatory” (italics in original).

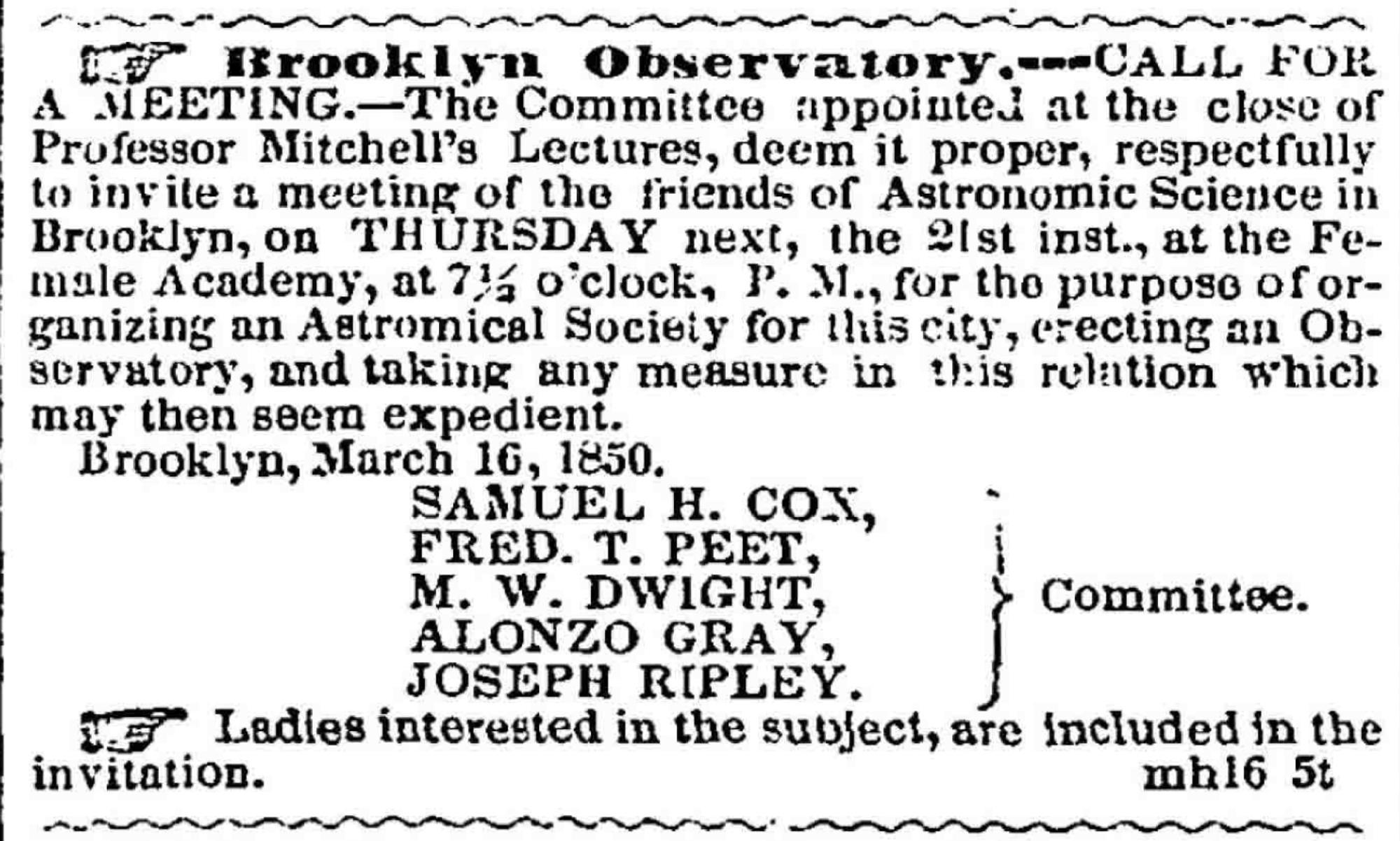

Classified ad in the March 16, 1850 issue of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle announced a meeting following one of O. M. Mitchel’s inspirational lectures, to discuss a second attempt to build a major astronomical observatory in Brooklyn. The ad expressly stated that women were invited.

Two separate attempts were made in 1847 and 1850 to raise the projected budget of $40,000.

In 1847, the Brooklyn Observatory committee recommended that “the sum be divided into 800 shares of 50 dollars each,” one share making the subscriber a member of the Brooklyn astronomical association. No subscription would become payable until all eight hundred shares were pledged. The project was strongly supported by many Brooklyn leading lights, including the not-yet-famous twenty-six-year-old editor of the Daily Eagle, Walt Whitman, who wrote an anonymous editorial titled, "That Observatory in Brooklyn which we MUST have.”

The Brooklyn Observatory committee did in fact invite Mitchel to deliver a series of lectures in December 1847 to support fundraising. After his final lecture, the observatory committee reported that “about $13,000 had been subscribed, and some $2,000 more pledged.” Another $1,000 was pledged a few days later. Despite the concrete steps and fundraising progress of $16,000, momentum flagged and they were unable to reach the full $40,000. The effort went into hibernation.

In the spring of 1850, when Mitchel gave another series of lectures in Brooklyn, the observatory effort was revived. This time, the fundraising target was cut in half: shares were offered at $25 apiece, with subscriptions to become binding when just $20,000 was pledged. Moreover, a fundraising circular acknowledged that New York City and Brooklyn are “virtually one community,” so “we expect from our wealthy senior city, New York, at least an aggregate of $15,000 to $20,000.”

For an observatory site, property owner Judge John Vanderbilt offered a hill 168 feet high plus three adjoining acres near Flatbush (which parcel later became part of Prospect Park). In November, Mitchel was back in Brooklyn giving another course of lectures. The ultimate figure subscribed, however, never topped the original $16,000—and no outlays could be committed until the minimum financing was secure.

The next year (September 1851), the enterprise was formally abandoned, and provisions made for subscribers’ money to be returned. “The second attempt to establish an astronomic observatory in our city appears to have failed,” lamented the Daily Eagle, “and the spirit by which it was started to have died away.”

In late 1858, the New York City mayor, several university trustees and professors, and other prominent Manhattan citizens launched a city-wide fundraising campaign to found a New York Astronomical Observatory in the brand new Central Park, both “for popular use, and for scientific research” (their emphasis). Estimated to need a budget of $200,000 for a record-breaking eighteen-inch refractor and ten smaller instruments, its stated goal was to “be worthy to compare with the great Observatories of Europe.”

The organizers immediately invited Mitchel to give a course of five lectures in January 1859, “to awaken and extend public interest in the object.” All proceeds from ticket sales would go toward the project. The fundraiser was a resounding success, with capacity crowds of “at least four thousand persons.”

But the nation was on the rumbling brink of the Civil War; Mitchel would serve as a Union general, dying in 1862. In the 1860s, a modest Central Park observatory was established primarily for meteorology, but no permanent astronomical instruments were mounted. Several proposals for a scaled-down observatory were considered, but none came to pass. The board of directors was dissolved in 1870.

*

By early 1888, Brooklyn was the second largest city in the US. The recently founded Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences had ambitions—and backing—to become the cultural center for the city. In May 1888 the Brooklyn Institute absorbed a well-connected Brooklyn astronomical society, which became the institute’s astronomical department.

The Brooklyn Institute acquired land and founded what is now the Brooklyn Museum. Its original vision was for a museum four times larger than today’s building, which was also to include a “first class observatory.” Floorplans for the prospective Brooklyn Museum published in 1894 included an “Observatory Annex,” originally sited to the southeast of the main building but later relocated to the southwest of it. The New York State legislature approved the new site in 1906 and appropriated $150,000 for construction; the new plan was also approved by the Superintendent of Parks, the New York City mayor, and signed into law by the New York state governor—in short, all legal approvals and financing were secured.

However, in 1907, popular astronomy writer Garrett P. Serviss (1851–1929), stepped down from his position as the institute’s long-serving astronomical department president. In 1908, a major economic recession swept the nation, suspending work on the observatory. Six years later, after the start of the “Great War,” energetic Brooklyn Institute president and Brooklyn Museum founder—and leading observatory advocate—Franklin W. Hooper (1851–1914) died.

*

Astronomical observatories that were planned but never constructed are historically significant because they reflect the full depth of nineteenth-century America’s yearning for them, even if those aspirations never materialized in glass and brass. The failed attempts also reveal cautionary lessons for future ones.

All three observatories were envisioned to be major facilities, and all three took serious steps toward that aim (issuing prospectuses, acquiring land, and raising funds). Both the Brooklyn Observatory and the New York Astronomical Observatory in Central Park modeled the structure of their subscription financing on Mitchel’s Cincinnati fundraising, and directly involved Mitchel himself. Both the Central Park observatory and the Brooklyn Museum proposals secured the support of nationally renowned astronomers and major New York politicos, and the museum observatory was allocated significant state funding.

However, wider external forces—notably the Civil War and several nationwide economic panics—derailed the efforts. A concomitant factor may have been deterioration of observing conditions in the New York City area with increasing urbanization, nighttime illumination, and industrial pollution.

Internal, flawed decisions also sandbagged the attempts. The Brooklyn Observatory’s 1847 financial goal of $40,000 for a major observatory to be financed by the sale of eight hundred shares of stock at $50 per share was unrealistically high. Even halving the fundraising target in 1850 was not enough to attract adequate support. Moreover, the Brooklyn Observatory organizers did not have a local fundraiser as vigorous in pounding the pavements day after day as Mitchel had been in Cincinnati.

In contrast, the Brooklyn Museum observatory initially had strong leadership. However, execution was delayed for years by a preventable change in the location of the observatory site, which required new municipal and state approvals. The delays ultimately resulted in the loss of effective leadership through resignation and death (in contrast, the equally ambitious Children’s Museum and Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, both envisioned and approved at the same time, did get built).

It’s perhaps only fitting, given where that story left off, that the historic telescope acquired by Pioneer Works dates from that same era––the height of America’s most productive industrial age. To magnify astronomical images, the nearly sixteen-foot long telescope focuses light with a historic 12.5-inch refractor and has a lens made by one of the era’s top opticians, John A. Brashear. The instrument is supported on a several ton mount by the iconic telescope manufacturers Warner & Swasey. When it was first installed in 1895 in the Emerson McMillin Observatory of the Ohio State University, it was the largest refracting telescope in Ohio at the time, and the instrument acquired the nickname “The McMillin.” It’s now being restored to its original glory. Construction is underway to fortify the roof while the building is undergoing upgrades to modern accessibility standards as we prepare for the future observatory. The intention is to mount the restored telescope as the centerpiece of what will be, when it opens, the first public observatory of its kind in the city that never sleeps. ♦

Donate to Pioneer Works in support of the observatory campaign here or write to us at science@pioneerworks.org. Special thanks to Bart Fried for sharing the photos he uncovered of the McMillin Observatory.

Subscribe to Broadcast